The Scoop on Yin Yoga

By Tracey Soghrati

Why is it called Yin Yoga?

The word yin can be defined as a polarity that exists in all of natural phenomenon. More specifically, in Chinese cosmology it is likened to passive, feminine energy. It is often described as darker, slower, and more internal. Yang, as it’s opposite is characterized as active masculine energy. It is often described as faster, brighter and more superficial. The two co-exist as dynamic concepts representing the relationships in the natural world, which both control and define each other.

When practicing yoga in a yin way, we simply take postures that we are familiar with and practice them with less effort and with less movement for a longer period of time (about 2-5 minutes/posture). So it’s sometimes referred to as a passive-static method of stretching. If we practice yoga in a yang way, it is faster, more dynamic and less passive (think of “power yoga”, “ashtanga yoga”, “jivamukti yoga”).

Does naming this style of yoga “Yin” ever cause misconceptions?

The short answer to this question is YES.

In calling a style of yoga “yin” in nature, we cleverly imbue all the characteristics of that practice with the aforementioned attributes. Unfortunately, while the correlation works most of the time, it becomes tricky when practitioners get overly invested in the name and lose sight of what is actually happening in the body. What I mean by this is that calling a yoga practice yin doesn’t automatically mean that the tissues assume and behave in the way that this philosophy predicts. For example, yin qualities are cold, dark, and feminine – but it doesn’t literally mean that this practice has to be cold, dark and feminine. Calling the practice “yin” simply means that it is slower and more passive when compared to other practices.

This literal and polarized thinking also shows up in the following statement: ‘yang yoga targets the yang tissues – the muscles’, while ‘yin yoga targets the yin tissues, the connective tissues’. Please note that I myself used to teach this, but with a little critical thinking we can assess what is actually happening so that teachers and students alike are not mislead. It is impossible to segregate the body into discrete sections on our own say-so, particularly just because we are trying to shift a live practice into a philosophical system. In reality, all of these tissues are so entwined and integrated that it is nearly impossible to affect one type of tissue without an effect on the other types. It would be more accurate to state that each style of yoga (passive vs. dynamic) affects the whole body in different ways (like cross-training), while having more targeted effects on some specific tissues.

More specifically, when we engage in a passive static stretch, both the muscle and connective tissues in the body behave in a viscoelastic (or time-dependent) way – they deform over time, and that deformation resolves if we haven’t gone too far (more about this later). We can also say that practicing yoga postures in a passive-static (yin) way is one method of ensuring the overall health of our tissues, and it does this by enhancing fascial fitness.

What is Fascial Fitness?

When it comes to movement, we rely on a balance between strength/stability and flexibility/mobility and we achieve this by working with the myofascial web – so the muscle and all of its connective tissue together. According to Dr. Robert Schleip, the best way to achieve graceful, fluid movement that is also strong and stable is to encourage fascial fitness in the body. His research suggests that we can enhance our range of motion, performance and the hydration of the tissues through the following: long held static stretches, dynamic stretching (non-linear and playful) with muscular engagement, muscular action with bouncing movement and a variety of therapies ranging from ball-rolling to rolfing to osteopathy. As one facet of the picture, slow melting stretches are excellent because the whole muscle unit is elongated and relaxed which allows access to deeper layers of intramuscular fascia.[1] By accessing these deeper layers, we rehydrate the tissue and allow for a more youthful architecture to develop. Interestingly research has also demonstrated that as we age (especially for women and those over 65) longer held static stretches (>1 min) are more efficacious in enhancing ROM.[2]

Loading to strengthen and not to lengthen: Props are good

The key to hitting the sweet spot in this practice is in how you load the tissues. There’s a phenomenon that happens in the tissue whereby it will deform continuously over time and under a constant load. So for example, say you’re seated on the floor, legs extended and you fold forward by flexing or rounding the spine. The tissue being deformed (stretched) is at the back of the body and the load is your body weight (head and torso) coupled with gravity. So the load is constant and as you hang forward, the tissue will continue to lengthen – the more lengthening you get, the less stability you have. Now if you add a prop in (think a bolster or pillow under the belly), the load is still the same, but the tissue can’t lengthen, so it will actually strengthen (continue to bear the load without getting longer). In short, this is why props are good in a yin yoga practice. Too much lengthening will sacrifice your integration.

Rethinking the rebound – what is creep?

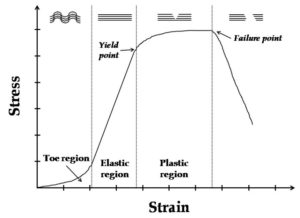

If we go back to the idea of the tissue continuously lengthening under a constant load, what we have is a concept called “creep”. I actually love that name – it feels so right. The tissue creeps (gets longer) gradually over time if the load is constant and this can have a number of effects. First of all, as we stretch (deform) over time, there is a relative safety zone that is more elastic – meaning that when we come out of the stretch, the body will begin to recover. However, that recovery is super slow. If you’ve done a variety of postures that place your body in flexion for about 20 minutes, you would need more than double that time for about 70% recovery.[3] Moreover, if we lengthen too much we might move beyond the elastic region of the tissues and into the plastic region. This is when we are deforming the tissue in a permanent way and it can move us into injury (see the chart).

I’ve heard teachers comment that the time in between yin yoga postures should be savoured as the experience of tissue rebound, but as I mentioned above, this isn’t really what’s happening. As an alternative view I feel that the time in between yin yoga postures is best spent mindfully integrating the experience. And for many people this means cultivating an awareness of the way that the parasympathetic nervous system has been facilitated by moving and breathing slowly. Moreover, some people might have the urge to move in between postures (by contracting the muscles) and this may serve as a way to integrate the tissues, however, without properly studying this concept we can’t say that with authority.

Adjustments can be Dicey in yin yoga

I love adjustments. Touch can be incredibly informative and therapeutic in dynamic classes when it is applied with consent and supported by adequate training in assessment. However, when a practitioner is holding slow melting stretches for 5 minutes at a time, no teacher has the ability to determine if they are stretching into their plastic region. And if a teacher comes along and adds force to tissue that is already deformed into the plastic region, just as the pretty graph indicates above, it will tear. So my general rule in a yin yoga class is no adjustments. This doesn’t equal no touch – if you massage their necks at the end of class or assist with props, go crazy, but don’t add any force in the postures as it’s too risky.

Yang to the Yin

In all the years I’ve practiced yoga, this is my favourite way to do it. Yang to Yin classes simply start with dynamic movement that works on both range of motion and strength, and culminate in slow melting stretches. From a physiological standpoint, this is the best way to ensure fascial fitness as defined by Schleip – it’s the most bang for your buck. But it also feels REALLY AMAZING. By starting the class vigorously, we have the opportunity to blow off all of our anxiety. Exercise produces endorphins (endogenous morphine) and this helps to move us into the present moment so that we can actually be receptive to slowing down (and we’ve strengthened the body for at least 30 minutes). As we move into the passive postures the nervous system has been prepared for relaxation by focused attention and steady breathing, so we can literally just drop into it. This paves the way for mindfulness, insight and self-reflection!

[1] Schleip, Robert. (2014). Fascial Fitness: How to be Resilient, Elegant and Dynamic in Everyday Life and Sport. Lotus Publishing

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3273886/ Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012 Feb; 7(1): 109–119.PMCID: PMC3273886 CURRENT CONCEPTS IN MUSCLE STRETCHING FOR EXERCISE AND REHABILITATION

Phil Page, PT, PhD, ATC, CSCS, FACSM

[3] Solomonow, M. Ligaments: A source of musculoskeletal disorders. Anatomy, physiology, pathophysiology review. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2009 (13):136-154.

[4] https://www.intechopen.com/books/theoretical-biomechanics/biomechanics-and-modeling-of-skeletal-soft-tissues